LAKE CHARLES - As Terrance Prudhomme walks down his block in a neighborhood just north of I-10, he points out one empty home after the other. That red brick house with the scraps of blue tarp on the roof? He hasn’t seen the owners in months. The small cottage next door? Same deal.

“It’s like the Twilight Zone. There’s nobody here,” Prudhomme said.

The 52-year-old is one of the few residents that remain on his block in North Lake Charles, where the destruction wreaked by hurricanes Laura and Delta, as well as a May 2021 flood, is still evident.

"This used to be a community," Terrance Prudhomme said, pointing at the empty lots and abandoned homes that now make up much of his block in North Lake Charles.

Since the storms, he has worked on fixing his late mother’s house. Next door, in tatters, sits the home his grandfather built, where generations of his family were raised. He wants to save that too, but the clock is running out.

Like other Louisiana cities following disasters – and especially New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina – Lake Charles is grappling with how to deal with the damaged homes left behind and which remain unrepaired years later. While it is tempting for cities to simply bulldoze them, concerns related to fairness to cash-strapped owners and legalities complicate the process.

The pine wood home Prudhomme is trying to save is one of hundreds of properties that have come before the Lake Charles City Council over the past year to decide whether the city should order it to be demolished. Every month, dozens of properties fill the agenda, many of them damaged by hurricanes and still in varying states of disrepair more than two years later.

The stoop of Terrance Prudhomme's family home, which was severely damaged by Hurricane Laura.

This is how the process works: The city is notified of a property that is severely damaged, either by neighbors or an inspector in the field. City staff then notify the recorded owner or owners who have two weeks to respond. If there is no response or staff concludes that the property might still have to be demolished by the city, it’s placed on the agenda for a vote.

“You can’t let them sit in that condition forever. It’s not fair to the property owners in the neighborhood or the person living next door,” City Administrator John Cardone said. If the owners fail to fix or clean up damaged structures on their property, the city can tear them down, the cost of which is placed on the property as a lien.

“After the hurricanes, the city was more lenient, the council was more lenient,” Cardone said. But since last summer, orders for demolition have picked up. “We’ve taken a bit of a more aggressive approach,” Cardone added. “It’s been a few years.”

The home of Danny Jay's late mother, where he was living before evacuating, has sat in disrepair since the storm. Jay said he hasn't been able to afford repairs and was turned down by programs offering assistance.

But some property owners say they still need more time, including Danny Jay, 37, whose home was severely damaged by Laura. Jay and his brother inherited the home after his mother died of breast cancer in 2008 and paid it off with the rest of their inheritance.

“When my mom was in the hospital, when she was dying, she told us: ‘I don’t want y’all to lose the house,’” Jay remembers. “That was a big thing.”

And for over a decade, he was able to make good on his promise. Then came Laura.

The damages to the home, where Jay had been living until he evacuated prior to the storm, were substantial. A fallen tree completely wrecked the carport, parts of the roof were torn off.

Jay said he couldn’t afford insurance prior to the storm and the repairs are more than he could swing working as a salesman for a beer distributor. FEMA gave him $2,800, an assessment that suggests there wasn’t any major damage. So when he applied for the state’s Restore program, set up to administer federal funds to help homeowners rebuild, he was denied. He applied for aloan from the U.S. Small Business Administration, which also provides post-disaster help, but was denied there too.

“Anytime something like that happens, there’s people that fall through the cracks,” Jay said. “I kept getting turned down by everyone.”

Daniel Jay, 37, stands in the backyard of his late mother's home, which was severely damaged by Hurricane Laura in August 2020.

When he first heard that the city was looking at ordering the demolition of the home in January, he got a second job at the UPS store the same week to try and save up more money for repairs. He has torn down the carport and, whenever he can, he pays someone to remove debris and keep the vegetation in check.

“I’m trying to do the right thing, but I’m stuck,” Jay said.

Without a clear path toward fixing the house, his efforts only go so far. The council agreed to give Jay more time, but without the funds for major repairs and without a buyer in sight, demolition is likely his only option.

“I just don’t feel like being forced into the position,” Jay said. “And it seems like that’s what they’re doing to people.”

Cardone said it’s a tough balance to strike for the city. “There’s a fine line. You do everything to work with that individual to try and point them in the right direction,” he said. “But sometimes there’s nothing we can do.”

And, “we can’t let the city continue to look the way it looks,” Cardone said.

Prudhomme said he understands that the city wants to clean up neighborhoods and rebuild. But he thinks there need to be more pathways to assistance for people like himself and his neighbors.

"It's solid," Terrance Prudhomme, 52, said knocking on the walls of the pine-wood home his grandfather built. He's hoping to save it, but the city's is telling him it's time to tear it down.

“You have all this money and nobody is getting any help,” he said, referring to more than $1 billion in federal disaster aid gradually being distributed to those who qualify.

Next door, his neighbor, a disabled veteran, still lives with concrete floors and blankets for doors. He has applied for the city’s program to fix hurricane-damaged homes, but is still waiting for repairs to be made.

Meanwhile Prudhomme was denied any assistance. After the deaths of several older relatives, the question of who owns the house has become complicated, making him ineligible for the most common assistance programs, all of which require a clear title.

This problem, which the city acknowledges is one of the main issues when it comes to fixing homes and preventing them from being demolished, is especially prominent in areas of the city that are predominantly Black, says community organizer Tasha Guidry.

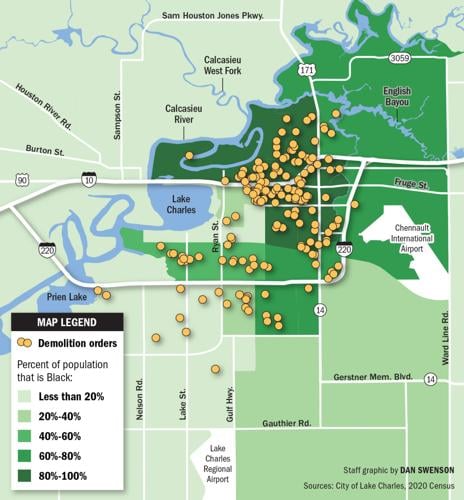

City-ordered property demolitions: If owners don’t fix or tear down their hurricane-damaged properties, Lake Charles city officials can order them demolished. The density of properties on which those orders have been issued is especially high in primarily Black neighborhoods.

Guidry recently held an estate planning workshop to help residents fix ownership issues that prevent them from accessing help.

“A lot of people are missing the ability to apply for Restore because they never did the legal work after someone passed,” she said. “So it’s leaving people not having the money to do anything with those properties and so they have no recourse but to just allow the city to tear them down.”

The problem, Guidry says, lies with access to resources and information, and a need for more education around administrative processes like succession planning. “There’s so much of a disconnect between the governing agencies and the community,” she said.

One of many abandoned home on the North Lake Charles street where Terrance Prudhomme lives and is trying to save his family home from demolition.

The Restore program, the largest source of funding to repair and replace homes damaged by the natural disasters that damaged tens of thousands of homes in Louisiana over the past three years, has been struggling to find enough people to spend its funds on, and has recently amped up its outreach and eased eligibility requirements in response.

Changes to the program's eligibility and efforts to clear up ownership issues might also mean that more people, including Prudhomme and Jay, could still become eligible for help — if their homes haven't been demolished by then.

Meanwhile, without a clear pathway to help, many residents, like those on Prudhomme’s block, have abandoned their properties. In many cases, no one shows up to contest when those properties are put up for demolition in front of the city council. “Everybody just gave up and left,” Prudhomme said.